netquirks

Exploring the quirks of Network Engineering

All stitched up

Segment Routing is undoubtedly one of the most powerful tools in modern Service Provider networking. It introduces a source-based routing paradigm that allows ingress routers to stack instructions or “segments” onto packets. Using this you can steer traffic through a network without the need for the signalling and state management that comes with traditional MPLS Traffic Engineering.

This blog explores a scenario where traffic is steering into two sequential SR policies – essentially stitching them together. It assumes a solid understanding of the basic functionality of MPLS based Segment Routing.

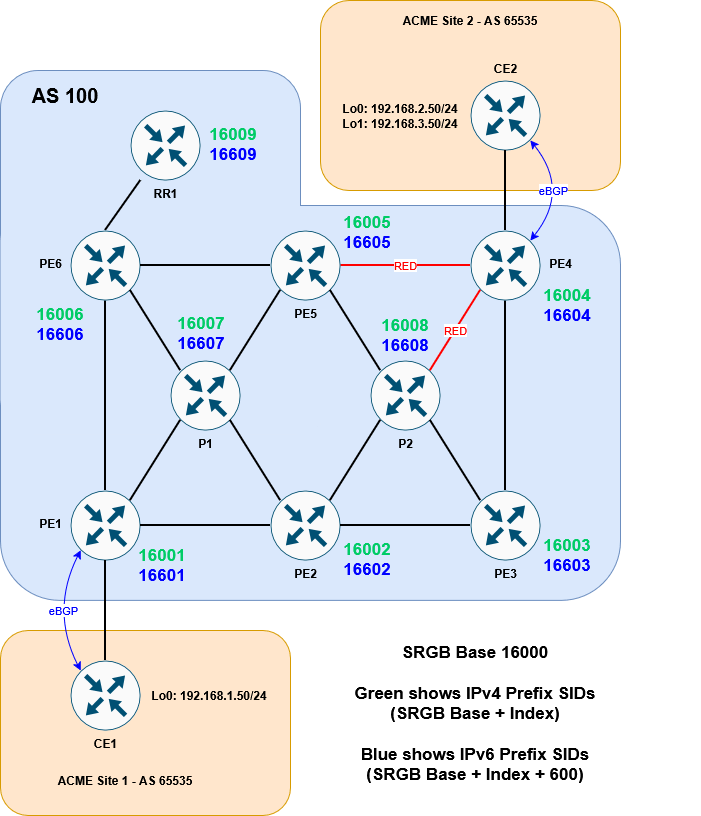

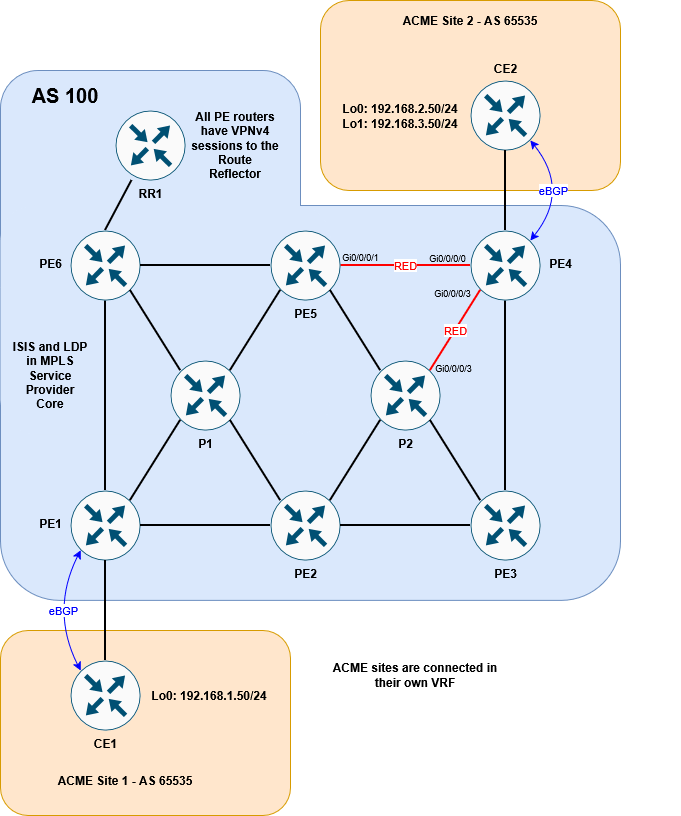

Here is the topology we will be working with:

It’s a basic MPLS network, running ISIS + LDP in the core. VPNv4 routes are exchanged via the router reflector. CE1 and CE2 are customer devices connected via BGP to the Service Provider – placed inside VRF ACME.

I’ve built this lab in EVE-NG. If you have your own setup, you can download the lab and/or config files here to follow along:

The EVE-NG lab consists of:

11 x Cisco XRv 9k 7.9.2s and 2 x Cisco XE 17.03.02s

Login creds are user1/user123

The goal

As mentioned above, our goal here is to connect two SR policies together. The first policy will direct traffic from PE1 to PE5 using an explicit path. The second policy will direct traffic from PE5 to PE4 by dynamically avoiding red colored links.

Here it is in diagram form:

Whilst this is only a lab environment, this kind of traffic engineering could be used in larger environments to do tasks such as steering traffic towards DDoS scrubbers, avoiding maintenance links or crossing administrative boundaries.

If we were using MPLS RSVP to signal the separate paths, all the LSRs would need to reserve and maintain the required state. This would be done using RSVP Path or Resv message (more details here). Segment Routing can accomplish this much more efficiently.

We’ll begin by looking at the base state of the network, then walk through the steps to enable SR, before finally creating the policies.

The setup

Let’s start by checking out the ISIS and LDP config. Here is a sample from PE1:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#sh run router isis

Fri Nov 7 20:20:35.436 UTC

router isis ISIS1

is-type level-2-only

net 49.0001.0100.0000.0001.00

mpls ldp sync

address-family ipv4 unicast

metric-style wide

advertise passive-only

mpls ldp auto-config

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

metric-style wide

advertise passive-only

single-topology

!

interface Loopback0

passive

address-family ipv4 unicast

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

!

!

interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0/0

point-to-point

address-family ipv4 unicast

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

!

!

interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0/2

point-to-point

address-family ipv4 unicast

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

!

!

interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0/3

point-to-point

address-family ipv4 unicast

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

!

!

!

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1# PE1 has a VRF called ACME configured with a BGP session to the CE2:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#sh run router bgp

Fri Nov 7 20:21:03.711 UTC

router bgp 100

address-family vpnv4 unicast

!

address-family vpnv6 unicast

!

neighbor-group RR

remote-as 100

update-source Loopback0

address-family vpnv4 unicast

!

address-family vpnv6 unicast

!

!

neighbor 10.1.1.9

use neighbor-group RR

!

vrf ACME

address-family ipv4 unicast

!

address-family ipv6 unicast

!

neighbor 172.16.1.2

remote-as 65535

address-family ipv4 unicast

route-policy ALLOW-ALL in

route-policy ALLOW-ALL out

as-override

!

!

neighbor 2001:ce1::2

remote-as 65535

address-family ipv6 unicast

route-policy ALLOW-ALL in

route-policy ALLOW-ALL out

as-override

!

!

!

!

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1# sh bgp vrf ACME neighbors 172.16.1.2 routes

Fri Nov 7 20:21:23.859 UTC

BGP VRF ACME, state: Active

BGP Route Distinguisher: 100:1

VRF ID: 0x60000001

BGP router identifier 10.1.1.1, local AS number 100

Non-stop routing is enabled

BGP table state: Active

Table ID: 0xe0000001 RD version: 10

BGP main routing table version 10

BGP NSR Initial initsync version 4 (Reached)

BGP NSR/ISSU Sync-Group versions 0/0

Status codes: s suppressed, d damped, h history, * valid, > best

i - internal, r RIB-failure, S stale, N Nexthop-discard

Origin codes: i - IGP, e - EGP, ? - incomplete

Network Next Hop Metric LocPrf Weight Path

Route Distinguisher: 100:1 (default for vrf ACME)

Route Distinguisher Version: 10

*> 192.168.1.0/24 172.16.1.2 0 0 65535 i

Processed 1 prefixes, 1 paths

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#The same type of session is configured between PE4 and CE2. This is all fairly stock standard for a Service Provider environment. We can demonstrate the basic MPLS network by running a traceroute from CE1 to CE2 (sourcing with CE1 Loopback 0 to emulate a LAN).

(NB. For the sake of this lab, the label ranges for each if the LSRs have been set to 24×00 – 24×99, where x is the identifier for that router – PE1 has identifier 1 etc.)

CE1#traceroute 192.168.2.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.2.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 3 msec 2 msec 2 msec

2 10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 24607/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.17.7 [MPLS: Labels 24707/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec 4 msec

3 10.10.57.5 [MPLS: Labels 24507/24407 Exp 0] 3 msec

10.10.56.5 [MPLS: Labels 24507/24407 Exp 0] 3 msec 3 msec

4 10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.48.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 3 msec

10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 3 msec

5 172.16.2.2 3 msec * 5 msec

CE1#You can see the traffic is taking a standard ECMP path through the network. Now let’s look at getting SR working

Setting up SR

Enable Segment Routing

The first step is to enable SR and assign prefix SIDs (don’t forget to enable mpls traffic engineering router-id as well!).

We’ll set the SRGB base to be 16000 across all devices and give sequential IPv4 indexes to each router (PE1 will be SID index 1 etc.). The IPv6 indexes will be the same but +600.

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:23:21.489 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#router isis ISIS1

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis)# address-family ipv4 unicast

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# segment-routing mpls sr-prefer

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# router-id lo0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# !

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# address-family ipv6 unicast

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# segment-routing mpls sr-prefer

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# router-id lo0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# !

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-af)# interface Loopback0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if)# address-family ipv4 unicast

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# prefix-sid index 1

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# !

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# address-family ipv6 unicast

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# prefix-sid index 601

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# !

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)# !

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)#!

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis-if-af)#segment-routing

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr)# global-block 16000 23999

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:24:01.542 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:Nov 7 20:24:03.706 UTC: bgp[1094]: %ROUTING-BGP-2-SR_CFG_CHANGED : SRGB range config has been changed. BGP's labels have to be re-programmed as per new range, 'process restart bgp' needed

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#I’ve enabled the router ID using the router-id lo0 command here, which works under ipv4 and ipv6. An alternative is to use mpls traffic-eng router-id lo0. This might already be in place if you are migrating from traditional MPLS-TE, but it’s only applicable to the ipv4 address-family.

Once we repeat this for all the Service Provider routers, we can see that the MPLS forwarding table now prefers Segment Routing:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#sh mpls forwarding

Fri Nov 7 20:29:20.862 UTC

Local Outgoing Prefix Outgoing Next Hop Bytes

Label Label or ID Interface Switched

------ ----------- ------------------ ------------ --------------- ------------

16001 Aggregate SR Pfx (idx 1) default 0

16002 Pop SR Pfx (idx 2) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

16003 16003 SR Pfx (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

16004 16004 SR Pfx (idx 4) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

16004 SR Pfx (idx 4) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

16004 SR Pfx (idx 4) Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

16005 16005 SR Pfx (idx 5) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

16005 SR Pfx (idx 5) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

16005 SR Pfx (idx 5) Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

16006 Pop SR Pfx (idx 6) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

16007 Pop SR Pfx (idx 7) Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

16008 16008 SR Pfx (idx 8) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

16009 16009 SR Pfx (idx 9) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

16601 Aggregate SR Pfx (idx 601) default 0

16602 Pop SR Pfx (idx 602) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

16603 16603 SR Pfx (idx 603) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

16604 16604 SR Pfx (idx 604) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

0

16604 SR Pfx (idx 604) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

16604 SR Pfx (idx 604) Gi0/0/0/2 fe80::5200:ff:fe04:5 \

0

16605 16605 SR Pfx (idx 605) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

0

16605 SR Pfx (idx 605) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

16605 SR Pfx (idx 605) Gi0/0/0/2 fe80::5200:ff:fe04:5 \

0

16606 Pop SR Pfx (idx 606) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

0

16607 Pop SR Pfx (idx 607) Gi0/0/0/2 fe80::5200:ff:fe04:5 \

0

16608 16608 SR Pfx (idx 608) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

16609 16609 SR Pfx (idx 609) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

59

24100 24600 10.1.1.9/32 Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

24101 Pop 10.1.1.6/32 Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 196

24102 24601 10.1.1.5/32 Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

24204 10.1.1.5/32 Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24703 10.1.1.5/32 Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

24103 Pop 10.1.1.7/32 Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 98

24104 24201 10.1.1.8/32 Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24105 24206 10.1.1.3/32 Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24106 Unlabelled 192.168.1.0/24[V] Gi0/0/0/1 172.16.1.2 0

24107 Unlabelled 2001:ac73:1::/64[V] \

Gi0/0/0/1 fe80::5200:ff:fe06:0 \

0

24108 Pop 10.1.1.2/32 Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 334

24109 24607 10.1.1.4/32 Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

24205 10.1.1.4/32 Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24707 10.1.1.4/32 Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

24110 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24111 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/3 10.10.12.2 0

24112 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

24113 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/0 10.10.16.6 0

24114 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

24115 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/2 10.10.17.7 0

24116 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

24117 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/3 fe80::5200:ff:fe05:6 \

0

24118 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

0

24119 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/0 fe80::5200:ff:fe02:4 \

0

24120 Pop SR Adj (idx 1) Gi0/0/0/2 fe80::5200:ff:fe04:5 \

0

24121 Pop SR Adj (idx 3) Gi0/0/0/2 fe80::5200:ff:fe04:5 \

0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1# And indeed, if we repeat our traceroute we can see that SR labels are now used:

CE1#traceroute 192.168.2.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.2.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 3 msec 1 msec 2 msec

2 10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec

10.10.17.7 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

3 10.10.56.5 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 3 msec 3 msec

10.10.57.5 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 3 msec

4 10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.48.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 3 msec

5 172.16.2.2 3 msec * 4 msec

CE1#ECMP is still in effect, but since the transport label stays as 16004 the whole way, we’d need to look at the IP addresses to determine the exact path.

Populate SRTE Database

From here we need to populate the SRTE database so that any dynamic policies (in our case the one that avoids RED links) can calculate their best path. This is done using the distribute link-state command under ISIS:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:30:46.177 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#router isis ISIS1

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis)#distribute link-state

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:31:05.594 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-isis)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#Once this is done across all the devices, we can see the topology by running the following command:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE2#show segment-routing traffic-eng topology

Fri Nov 7 20:32:16.003 UTC

Topology database:

------------------

Node 11

Router ID: 10.1.1.1

ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0001

Hostname: PE1

TE router ID: 10.1.1.1

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::1

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

SRGBs: 16000 - 24000

SRLBs: 15000 - 16000

Prefixes:

10.1.1.1/32

Regular SID index: 1

2001:1ab::1/128

Regular SID index: 601

Links:

Local: 10.10.12.1 Remote: 10.10.12.2

Remote node: ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0002

Hostname: PE2

TE router ID: 10.1.1.2

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::2

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

Metrics: IGP 10

Bandwidth: Total 125000000 Bps, Reservable 0 Bps

Adj-SIDs: 24111 (unprotected), 24117 (unprotected)

Local: 10.10.16.1 Remote: 10.10.16.6

Remote node: ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0006

Hostname: PE6

TE router ID: 10.1.1.6

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::6

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

Metrics: IGP 10

Bandwidth: Total 125000000 Bps, Reservable 0 Bps

Adj-SIDs: 24113 (unprotected), 24119 (unprotected)

Local: 10.10.17.1 Remote: 10.10.17.7

Remote node: ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0007

Hostname: P1

TE router ID: 10.1.1.7

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::7

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

Metrics: IGP 10

Bandwidth: Total 125000000 Bps, Reservable 0 Bps

Adj-SIDs: 24115 (unprotected), 24121 (unprotected)

<snip>

Node 19

Router ID: 10.1.1.9

ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0009

Hostname: RR1

TE router ID: 10.1.1.9

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::9

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

SRGBs: 16000 - 24000

SRLBs: 15000 - 16000

Prefixes:

10.1.1.9/32

Regular SID index: 9

2001:1ab::9/128

Regular SID index: 609

Links:

Local: 10.10.69.9 Remote: 10.10.69.6

Remote node: ISIS-L2 0100.0000.0006

Hostname: PE6

TE router ID: 10.1.1.6

IPv6 router ID: 2001:1ab::6

ISIS area ID: 49.0001

Metrics: IGP 10

Bandwidth: Total 125000000 Bps, Reservable 0 Bps

Adj-SIDs: 24909 (unprotected), 24911 (unprotected)

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE2#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE2#show segment-routing traffic-eng topology | inc "Node|Local|Bind"

Fri Nov 7 20:33:42.222 UTC

Node 11

Hostname: PE1

Local: 10.10.12.1 Remote: 10.10.12.2

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.16.1 Remote: 10.10.16.6

Hostname: PE6

Local: 10.10.17.1 Remote: 10.10.17.7

Hostname: P1

Node 12

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.12.2 Remote: 10.10.12.1

Hostname: PE1

Local: 10.10.23.2 Remote: 10.10.23.3

Hostname: PE3

Local: 10.10.25.2 Remote: 10.10.25.5

Hostname: PE5

Local: 10.10.27.2 Remote: 10.10.27.7

Hostname: P1

Local: 10.10.28.2 Remote: 10.10.28.8

Hostname: P2

Node 13

Hostname: PE3

Local: 10.10.23.3 Remote: 10.10.23.2

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.34.3 Remote: 10.10.34.4

Hostname: PE4

Local: 10.10.38.3 Remote: 10.10.38.8

Hostname: P2

Node 14

Hostname: PE5

Local: 10.10.25.5 Remote: 10.10.25.2

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.45.5 Remote: 10.10.45.4

Hostname: PE4

Local: 10.10.56.5 Remote: 10.10.56.6

Hostname: PE6

Local: 10.10.57.5 Remote: 10.10.57.7

Hostname: P1

Local: 10.10.58.5 Remote: 10.10.58.8

Hostname: P2

Node 15

Hostname: P1

Local: 10.10.17.7 Remote: 10.10.17.1

Hostname: PE1

Local: 10.10.27.7 Remote: 10.10.27.2

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.57.7 Remote: 10.10.57.5

Hostname: PE5

Local: 10.10.67.7 Remote: 10.10.67.6

Hostname: PE6

Node 16

Hostname: PE4

Local: 10.10.34.4 Remote: 10.10.34.3

Hostname: PE3

Local: 10.10.45.4 Remote: 10.10.45.5

Hostname: PE5

Local: 10.10.48.4 Remote: 10.10.48.8

Hostname: P2

Node 17

Hostname: PE6

Local: 10.10.16.6 Remote: 10.10.16.1

Hostname: PE1

Local: 10.10.56.6 Remote: 10.10.56.5

Hostname: PE5

Local: 10.10.67.6 Remote: 10.10.67.7

Hostname: P1

Local: 10.10.69.6 Remote: 10.10.69.9

Hostname: RR1

Node 18

Hostname: P2

Local: 10.10.28.8 Remote: 10.10.28.2

Hostname: PE2

Local: 10.10.38.8 Remote: 10.10.38.3

Hostname: PE3

Local: 10.10.48.8 Remote: 10.10.48.4

Hostname: PE4

Local: 10.10.58.8 Remote: 10.10.58.5

Hostname: PE5

Node 19

Hostname: RR1

Local: 10.10.69.9 Remote: 10.10.69.6

Hostname: PE6

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE2# All devices within the same domain should show the same output. We are now ready to start setting up the policies.

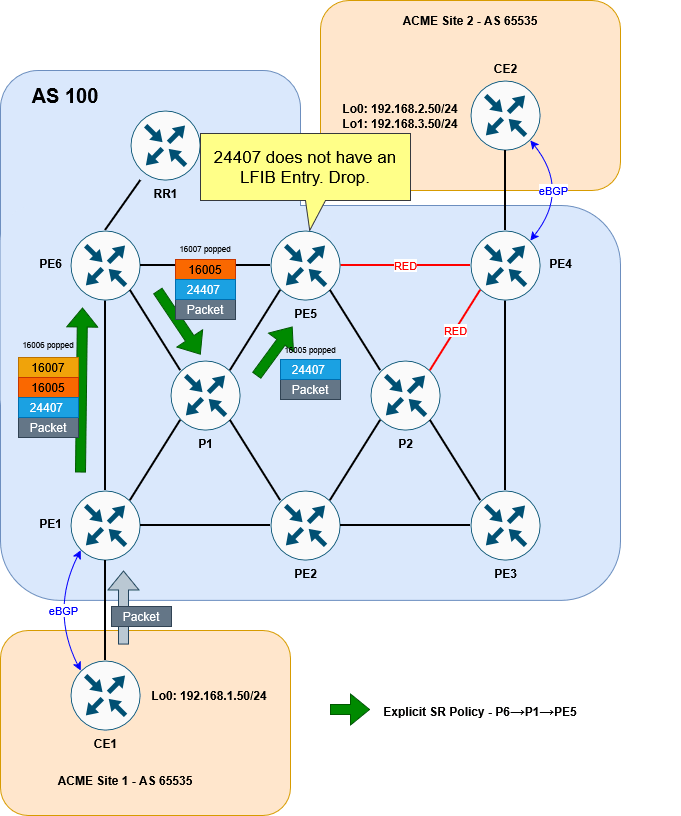

Configure explicit SR Policy

The first thing to do is set up an explicit segment list that details the path we want the traffic to follow. In our case the path looks like this:

Here is the CLI:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:34:54.088 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te)#segment-list name LIST-TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#index 10 mpls label 16006

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#index 20 mpls label 16007

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#index 30 mpls label 16005

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:34:59.279 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#With this done, we can create an SR policy to reference the explicit path:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:36:17.083 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te)#policy TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy)#color 10 end-point ipv4 10.1.1.5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy)#candidate-paths preference 100

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy-path-pref)#explicit segment-list LIST-TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-pp-info)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:37:23.704 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-pp-info)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#So far so good. Let’s verify that it has come up okay:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 10

Fri Nov 7 20:38:39.694 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 10, End-point: 10.1.1.5

Name: srte_c_10_ep_10.1.1.5

Status:

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:01:14 (since Nov 7 20:37:24.854)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (active)

Name: TO-PE5

Requested BSID: dynamic

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Explicit: segment-list LIST-TO-PE5 (valid)

Weight: 1, Metric Type: TE

SID[0]: 16006 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.6]

SID[1]: 16007

SID[2]: 16005

Attributes:

Binding SID: 24123

Forward Class: Not Configured

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: yes

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#We can see from the policy that it is up, but how do we steer traffic into it?

This is done by attaching a color community to the BGP router that matches the color of the policy. In our case, we’ll tag 192.168.2.0/24 inbound from CE2 with color 10

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:41:21.957 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config)#extcommunity-set opaque COLOR-10

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-ext)#10

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-ext)#end-set

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config)#route-policy FROM-CE2

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-rpl)#if destination in (192.168.2.0/24) then

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-rpl-if)#set extcommunity color COLOR-10

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-rpl-if)#endif

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-rpl)#pass

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-rpl)#end-policy

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config)#router bgp 100

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp)#vrf ACME

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf)#neighbor 172.16.2.2

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr)#address-family ipv4 unicast

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#route-policy FROM-CE2 in

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#Before we commit, here is what the prefix currently looks like in the BGP table:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#do show bgp vrf ACME 192.168.2.0

Fri Nov 7 20:41:50.516 UTC

BGP routing table entry for 192.168.2.0/24, Route Distinguisher: 100:1

Versions:

Process bRIB/RIB SendTblVer

Speaker 14 14

Local Label: 24407

Last Modified: Nov 7 20:41:20.501 for 00:00:30

Paths: (1 available, best #1)

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

Path #1: Received by speaker 0

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

65535

172.16.2.2 from 172.16.2.2 (192.168.3.50)

Origin IGP, metric 0, localpref 100, valid, external, best, group-best, import-candidate

Received Path ID 0, Local Path ID 1, version 14

Extended community: RT:100:1

Origin-AS validity: (disabled)

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#The additon of the color can be seen once we commit:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:42:10.086 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-bgp-vrf-nbr-af)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#show bgp vrf ACME 192.168.2.0

Fri Nov 7 20:42:19.644 UTC

BGP routing table entry for 192.168.2.0/24, Route Distinguisher: 100:1

Versions:

Process bRIB/RIB SendTblVer

Speaker 16 16

Local Label: 24407

Last Modified: Nov 7 20:42:12.501 for 00:00:07

Paths: (1 available, best #1)

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

Path #1: Received by speaker 0

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

65535

172.16.2.2 from 172.16.2.2 (192.168.3.50)

Origin IGP, metric 0, localpref 100, valid, external, best, group-best, import-candidate

Received Path ID 0, Local Path ID 1, version 16

Extended community: Color:10 RT:100:1

Origin-AS validity: (disabled)

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#Note that this has only been applied to 192.168.2.0/24, not 192.168.3.0/24:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#show bgp vrf ACME 192.168.3.0

Fri Nov 7 20:42:53.104 UTC

BGP routing table entry for 192.168.3.0/24, Route Distinguisher: 100:1

Versions:

Process bRIB/RIB SendTblVer

Speaker 15 15

Local Label: 24409

Last Modified: Nov 7 20:41:20.501 for 00:01:32

Paths: (1 available, best #1)

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

Path #1: Received by speaker 0

Advertised to PE peers (in unique update groups):

10.1.1.9

65535

172.16.2.2 from 172.16.2.2 (192.168.3.50)

Origin IGP, metric 0, localpref 100, valid, external, best, group-best, import-candidate

Received Path ID 0, Local Path ID 1, version 15

Extended community: RT:100:1

Origin-AS validity: (disabled)

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#PE1 sees the color as well:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#sh bgp vrf ACME 192.168.2.0/24

Fri Nov 7 20:43:32.410 UTC

BGP routing table entry for 192.168.2.0/24, Route Distinguisher: 100:1

Versions:

Process bRIB/RIB SendTblVer

Speaker 18 18

Last Modified: Nov 7 20:42:12.284 for 00:01:20

Paths: (1 available, best #1)

Advertised to CE peers (in unique update groups):

172.16.1.2

Path #1: Received by speaker 0

Advertised to CE peers (in unique update groups):

172.16.1.2

65535

10.1.1.4 (metric 30) from 10.1.1.9 (10.1.1.4)

Received Label 24407

Origin IGP, metric 0, localpref 100, valid, internal, best, group-best, import-candidate, imported

Received Path ID 0, Local Path ID 1, version 18

Extended community: Color:10 RT:100:1

Originator: 10.1.1.4, Cluster list: 10.1.1.9

Source AFI: VPNv4 Unicast, Source VRF: ACME, Source Route Distinguisher: 100:1

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#The idea here is for traffic to 192.168.20/24 to be directed into our color 10 tunnel. If this is working, we should see the CEF table on the ACME VRF recurving to the Binding SID for our SR Policy (if you look above, the Binding SID is 24123)…

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#show cef vrf ACME 192.168.2.0

Fri Nov 7 20:44:08.498 UTC

192.168.2.0/24, version 17, internal 0x5000001 0x30 (ptr 0xe9d5288) [1], 0x600 (0xd6f8dd8), 0xa08 (0xf549510)

Updated Nov 7 20:42:11.812

Prefix Len 24, traffic index 0, precedence n/a, priority 3

gateway array (0xd5524d8) reference count 2, flags 0x38, source rib (7), 0 backups

[3 type 1 flags 0x8441 (0xf583358) ext 0x0 (0x0)]

LW-LDI[type=1, refc=1, ptr=0xd6f8dd8, sh-ldi=0xf583358]

gateway array update type-time 1 Nov 7 20:41:19.728

LDI Update time Nov 7 20:41:19.729

LW-LDI-TS Nov 7 20:41:19.729

via 10.1.1.4/32, 5 dependencies, recursive [flags 0x6000]

path-idx 0 NHID 0x0 [0xd8bf740 0x0]

recursion-via-/32

next hop VRF - 'default', table - 0xe0000000

next hop 10.1.1.4/32 via 16004/0/21

next hop 10.10.16.6/32 Gi0/0/0/0 labels imposed {16004 24407}

next hop 10.10.12.2/32 Gi0/0/0/3 labels imposed {16004 24407}

next hop 10.10.17.7/32 Gi0/0/0/2 labels imposed {16004 24407}

Load distribution: 0 (refcount 3)

Hash OK Interface Address

0 Y recursive 16004/0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#But here, it looks like it is still just imposing 16004 (the SID for R4) and then 24407 (the VPNv4 label for 192.168.2.0/24). It’s then ECMP’ing it out of Gi0/0/0/0, Gi0/0/0/3 and Gi0/0/0/2.

So what gives? Why is it not using our SR Policy?

Well, we have to remember that the allocation of a prefix to a policy is based on the combination of the end-point and the color. Looking at the BGP route, the color is correct, but the end point (or next-hop in BGP talk) is still 10.1.1.4 – PE4. Our policy is defined as having an end-point of 10.1.1.5!

So let’s fix that:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:45:04.898 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te)#policy TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy)#color 10 end-point ipv4 10.1.1.4

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:45:31.664 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-policy)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#Now we see that it is correctly steering down the SR policy:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#sh segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 10 | inc "Operation|Bind"

Fri Nov 7 20:46:53.444 UTC

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:01:21 (since Nov 7 20:45:31.897)

Binding SID: 24125

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#show cef vrf ACME 192.168.2.0

Fri Nov 7 20:47:05.492 UTC

192.168.2.0/24, version 21, internal 0x5000001 0x30 (ptr 0xe9d5288) [1], 0x600 (0xd6f8dd8), 0xa08 (0xf54a068)

Updated Nov 7 20:45:31.910

Prefix Len 24, traffic index 0, precedence n/a, priority 3

gateway array (0xd553440) reference count 1, flags 0x38, source rib (7), 0 backups

[2 type 1 flags 0x8441 (0xf584328) ext 0x0 (0x0)]

LW-LDI[type=1, refc=1, ptr=0xd6f8dd8, sh-ldi=0xf584328]

gateway array update type-time 1 Nov 7 20:45:31.910

LDI Update time Nov 7 20:45:31.910

LW-LDI-TS Nov 7 20:45:31.910

via local-label 24125, 3 dependencies, recursive [flags 0x6000]

path-idx 0 NHID 0x0 [0xd8bb388 0x0]

recursion-via-label

next hop VRF - 'default', table - 0xe0000000

next hop via 24125/0/21

next hop srte_c_10_ep labels imposed {ImplNull 24407}

Load distribution: 0 (refcount 2)

Hash OK Interface Address

0 Y recursive 24125/0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#The Binding SID has changed to 24125 since we refreshed the endpoint, but CEF is looking good.

However, whilst this is steering the traffic into the policy, it still won’t get us all the way. If trace from CE1 we can see that we just get stars:

CE1#traceroute 192.168.2.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.2.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 47 msec 1 msec 2 msec

2 * * *

3 * * *

4 * * *

5 * * *

6 * * *

7 *

CE1#The reason for this is fairly simple. This is the stack we are putting on the packet to CE2:

16006 (PE6 Prefix SID)

16007 (P1 Prefix SID)

16005 (PE5 Prefix SID)

24407 (VPN label)

As each segment is completed, the top label is popped. We can very quickly see that when the packet reaches PE5 the VPN label is exposed. But PE5 has no idea what to do with it! This VPN label was allocated by PE4 not PE5!

For our solution, this is okay at this point in the setup. Remember we will be wanting to push this traffic into a second policy that avoids all RED links and does end up at PE4.

For now, and just for the sake of getting our traceroute working, let’s add the PE4 label to the bottom of our explicit stack, so that PE5 can forward traffic on to PE4. We’ll remove this later:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:49:52.903 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#segment-routing

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr)#traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te)#segment-list LIST-TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#index 40 mpls label 16004

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:50:03.914 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#Now a traceroute works correctly:

CE1#traceroute 192.168.2.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.2.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 3 msec 2 msec 2 msec

2 10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 16007/16005/16004/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec 3 msec 4 msec

3 10.10.67.7 [MPLS: Labels 16005/16004/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec 3 msec 3 msec

4 10.10.57.5 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 7 msec 3 msec 3 msec

5 10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 3 msec 3 msec 3 msec

6 172.16.2.2 3 msec * 5 msec

CE1#

For the explicit path to PE5 to work, we need to make sure that a label that PE5 is going to understand is exposed. To get that, we need to configure the second policy from PE4…

Configure dynamic SR Policy

This policy isn’t going to be explicitly defined. Rather, we’re going to define the conditions of the policy (namely to avoid red links) and let the head end router figure it out. The first step in creating a dynamic policy that avoids red links is to, well, configure some RED links!

As a reminder, these are the links we want to color red:

Before going any further, let’s get some clarity on the term color and the different ways it is used within the context of this lab.

Color

This scenario uses the term color to refer to multiple different things and it can get confusing if you don’t know what you’re looking at. The two ways we’re concerned with color are as follows:

Policy Coloring

The first, is the color that we have already seen when defining an SR policy. This is an identifier for the policy. If a prefix is tagged with that color (in the case of BGP, it will be an attribute) and its next-hop matches the policy endpoint, traffic to that prefix will be steered into the policy. This is exactly how we’ve steered traffic into our explicit tunnel at PE1.

Link Coloring

The second way in which color is used is with regards to link coloring. Coloring a connection between two devices works by using something called link affinities (also called Admin group from the MPLS TE RSVP days). When we entered the distribute-link state command above, ISIS started to advertise Segment Routing details in its TLVs. This includes details about the links themselves – like metric, delay and link affinities. The link affinity is basically a string made up of ones and zeros that we can set and use how we wish. In this case, we’re using the affinity to “color” a link. I put the word “color” in air quotes, because from a CLI perspective, the word color isn’t actually referenced. We engineers use the term color because it’s easy to visualise a link that way.

This section looks at the latter of the two color definitions. Within the CLI the link-affinity is referenced as an integer number. For our scenario, let’s make 7 represent RED. Here’s how it would look:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:52:55.870 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-te)#affinity-map name RED bit-position 7

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-te)#interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0/0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if)#affinity

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if-affinity)#name RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if-affinity)#interface GigabitEthernet0/0/0/3

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if)#affinity

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if-affinity)#name RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if-affinity)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:53:04.345 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4(config-sr-if-affinity)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#NB. As a side note, if you are configuring colors for different Flex-Algos, that config would go under the IGP (ISIS) and not under segment-routing. I won’t detail this here, but the principle of link coloring, with or without Flex-Algo, is the same.

Now that we’ve colored the link we can verify it:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4#show segment-routing traffic-eng topology | inc "Host|Link|Admin"

Fri Nov 7 20:54:14.682 UTC

<snip>

Hostname: PE4

Links:

Hostname: PE3

Hostname: PE5

Admin groups: 0x00000080 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

Hostname: P2

Admin groups: 0x00000080 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

<snip>

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE4# The output is a little messy, so I’ve piped the command and omitted the full result, but you can clearly see that the affinity bits (Admin groups) have been set for PE4’s links to PE5 and P2.

The next step would be to configure the policy on PE5 to avoid RED links. This looks similar to the explicit policy we used before but it instead uses the (surprise, surprise) dynamic keyword. We’ll give the policy a the color number of 20 (in the SR policy sense, not the link color sense), just to differentiate it from the PE1 – although colors will be locally significant:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#conf t

Fri Nov 7 20:57:40.548 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te)#policy AVOID-RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#color 20 end-point ipv4 10.1.1.4

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#candidate-paths preference 100

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy-path-pref)#dynamic

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-pp-info)#exit

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy-path-pref)#constraints

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-path-pref-const)#affinity

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-path-pref-const-aff)#exclude-any name RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-path-pref-const-aff)#commit

Fri Nov 7 20:57:45.688 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-path-pref-const-aff)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#Great. Now if we check the policy, we can see that it is up:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#sh segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 20

Fri Nov 7 21:15:12.580 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 20, End-point: 10.1.1.4

Name: srte_c_20_ep_10.1.1.4

Status:

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:06:00 (since Nov 7 21:09:12.560)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (active)

Name: AVOID-RED

Requested BSID: dynamic

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Affinity:

exclude-any:

RED

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Dynamic (valid)

Metric Type: TE, Path Accumulated Metric: 10

SID[0]: 16004 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.4]

Attributes:

Binding SID: 24529

Forward Class: Not Configured

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: yes

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#This might look to be working, but if you look at the SID list, it only appears to be adding 16004 onto the packet. This means it will simply send the traffic straight to PE4 without avoiding the RED links. To prove this, we can look at the LFIB forwarding behaviour for 16004. It just sends it out of the Gi0/0/0/1 interface (direct to PE4!)

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#sh mpls forwarding labels 16004

Fri Nov 7 21:15:41.648 UTC

Local Outgoing Prefix Outgoing Next Hop Bytes

Label Label or ID Interface Switched

------ ----------- ------------------ ------------ --------------- ------------

16004 Pop SR Pfx (idx 4) Gi0/0/0/1 10.10.45.4 10229

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#The reason for this is simple: The end that the link is colored on matters.

We’ve colored Gi0/0/0/0 and Gi0/0/0/3 on PE4. But nothing else.

Gi0/0/0/1 on PE5 isn’t colored RED. This might seem like a limitation, having to color both ends, but it allows traffic in different directions to take different paths, which could be handy depending on the circumstance. To help visualise this, it might be easier to think of the color as being applied to the outbound interface rather than the link as a whole. To put this in diagram form, this is what we’ve done:

So in our case, traffic from PE5 to PE4 will not be considered to be crossing a red link (but traffic from PE4 to PE5 would). We don’t need any multi-directional differences in our lab, so to make this consistent, let’s color the interfaces on PE5 and P2 facing PE4.

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#conf t

Fri Nov 7 21:16:19.448 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te)#interface gigabitEthernet 0/0/0/1

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-if)#affinity name RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-if)#commit

Fri Nov 7 21:16:23.781 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-if)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2#conf t

Fri Nov 7 21:16:56.984 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2(config)#segment-routing traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2(config-sr-te)#interface gigabitEthernet 0/0/0/3

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2(config-sr-if)#affinity name RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2(config-sr-if)#commit

Fri Nov 7 21:17:02.505 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2(config-sr-if)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:P2#With this corrected, here is what our policy on PE5 looks like:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 20

Fri Nov 7 21:17:26.918 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 20, End-point: 10.1.1.4

Name: srte_c_20_ep_10.1.1.4

Status:

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:08:14 (since Nov 7 21:09:12.560)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (active)

Name: AVOID-RED

Requested BSID: dynamic

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Affinity:

exclude-any:

RED

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Dynamic (valid)

Metric Type: TE, Path Accumulated Metric: 30

SID[0]: 16008 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.8]

SID[1]: 16003 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.3]

SID[2]: 16004 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.4]

Attributes:

Binding SID: 24529

Forward Class: Not Configured

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: yes

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#This is looking much better! The policy is going via PE3 (10.1.1.3), through P2 (10.1.1.8). It is using the Node SID of P2 first, then the node SID of PE3.

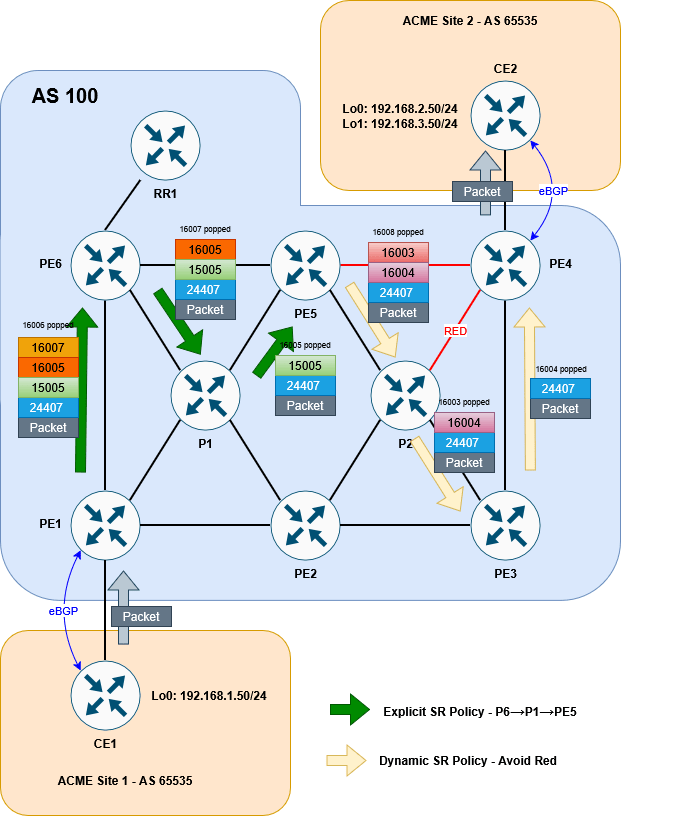

Stitching two policies together

Now that we’ve got both policies working, we need to stitch them together at PE5.

We’ve now got both of our policies working:

- The first policy will use an explicit path from PE1 to PE5

- The second policy will use a dynamic path from PE5 to PE4, avoiding red links.

We steered traffic into the first policy by tagging 192.168.2.0/24 with a color attribute 10, so that it matches the color (and endpoint) on PE1’s explicit policy.

But how do we steer traffic into our second policy. Well to understand this, we need to consider different ways that traffic is directed into SR policies:

Directing traffic into an SR Policy

An SR policy is all well and good, but it doesn’t mean much if you can’t actually steer traffic into it. We’ve already seen one way – namely by tagging a BGP route with the right color attribute. But there are other ways to accomplish this.

If the incoming packet is unlabelled you could use a static route, or some form of policy based routing – pseudowires can be configured to prefer a given SR policy etc.

But what we’re interested in here is how incoming labelled traffic enters an SR policy. Afterall, traffic coming from PE1 to PE5 on the explicit path will arrive with labels.

The way to steering labelled traffic into a SR policy is to use what is called the Binding SID of a given policy. The Binding SID is a locally significant label that instructs the router to steer any arriving traffic with that label into the SR policy. The incoming packet with the Binding SID on top, will have the Binding SID removed and then the labels associated with that policy imposed on to it.

We’ve already seen a form of this earlier when looking at the CEF entry for our first policy. The CEF entry showed the local Binding SID as being imposted. This will in turn apply the explicit segment list we specified.

So with this in mind, we need to make sure that traffic arriving at PE5 has the Binding SID for the SR policy that avoids red links. Re-checking the policy on PE5 shows that it has a Binding SID of 24529:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 20 | inc Binding

Fri Nov 7 21:18:31.185 UTC

Binding SID: 24529

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#The Binding SID is automatically generated and comes from a random pool – typically the same pool that LDP labels are pulled from. If PE5 were to reload, this number could change, meaning we’d have to change our policy on PE1. To avoid this, we can statically set the Binding SID as follows:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#conf t

Fri Nov 7 21:19:13.130 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config)#segment-routing

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr)#traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te)#policy AVOID-RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#binding-sid mpls 24500

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#commit

Fri Nov 7 21:19:19.346 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#RP/0/RP0/CPU0:Nov 7 21:19:29.482 UTC: xtc_agent[1292]: %OS-XTC-3-SR_POLICY_BSID_UNAVAIL : SR policy 'srte_c_20_ep_10.1.1.4' (color 20, end-point 10.1.1.4) binding-sid 24500 could not be allocated (BSID could not be allocated (check conflicts))

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 20

Fri Nov 7 21:19:53.463 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 20, End-point: 10.1.1.4

Name: srte_c_20_ep_10.1.1.4

Status:

Admin: up Operational: down for 00:00:24 (since Nov 7 21:19:29.483)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (inactive)

Name: AVOID-RED

Last error: BSID could not be allocated (check conflicts): 24500

Requested BSID: 24500

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Affinity:

exclude-any:

RED

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Dynamic (inactive)

Metric Type: TE, Path Accumulated Metric: 30

Attributes:

Forward Class: 0

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: no

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#Whoops. This doesn’t seem to have work. It’s unhappy with 24500, stating that there is a conflict. If we check our MPLS configuration we can see why:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#sh run mpls

Fri Nov 7 21:20:26.725 UTC

mpls ldp

!

mpls label range table 0 24500 24599

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#sh mpls label range

Fri Nov 7 21:20:42.978 UTC

Range for dynamic labels: Min/Max: 24500/24599

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#Our dynamic label range has been set to 24500 24599. This is from when we had LDP configured. We can’t set an explicit Binding SID from within a dynamic range. The Explicit binding SID should come from the SRLB which defaults to 15,000 – 15,999.

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#sh isis database verbose PE5.00-00 | inc Base

Fri Nov 7 21:21:03.444 UTC

Segment Routing: I:1 V:1, SRGB Base: 16000 Range: 8000

SR Local Block: Base: 15000 Range: 1000

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#We’ll allocate 15005 as the Binding SID:

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#conf t

Fri Nov 7 21:21:36.904 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config)#segment-routing

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr)#traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te)#policy AVOID-RED

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#binding-sid mpls 15005

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#commit

Fri Nov 7 21:21:41.223 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5(config-sr-te-policy)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 20

Fri Nov 7 21:21:46.905 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 20, End-point: 10.1.1.4

Name: srte_c_20_ep_10.1.1.4

Status:

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:00:05 (since Nov 7 21:21:41.348)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (active)

Name: AVOID-RED

Requested BSID: 15005

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Affinity:

exclude-any:

RED

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Dynamic (valid)

Metric Type: TE, Path Accumulated Metric: 30

SID[0]: 16008 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.8]

SID[1]: 16003 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.3]

SID[2]: 16004 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.4]

Attributes:

Binding SID: 15005 (SRLB)

Forward Class: Not Configured

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: yes

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE5#Brilliant. Now that we’ve got the Binding SID set, the final step is to change the policy from PE1 to ensure that when traffic arrives at PE5, it has SID 15005 on top.

Remember we previously added 16004 to PE1’s policy. This was just so that PE5 had something it recognised once traffic reached it and our test traceroute could work. We’ll remove that first and replace it with 15005.

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#conf t

Fri Nov 7 21:22:51.742 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config)#segment-routing

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr)#traffic-eng

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te)#segment-list LIST-TO-PE5

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#no index 40 mpls label 16004

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#index 40 mpls label 15005

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#commit

Fri Nov 7 21:22:57.593 UTC

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1(config-sr-te-sl)#

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#show segment-routing traffic-eng policy color 10

Fri Nov 7 21:23:02.044 UTC

SR-TE policy database

---------------------

Color: 10, End-point: 10.1.1.4

Name: srte_c_10_ep_10.1.1.4

Status:

Admin: up Operational: up for 00:37:30 (since Nov 7 20:45:31.897)

Candidate-paths:

Preference: 100 (configuration) (active) (reoptimizing)

Name: TO-PE5

Requested BSID: dynamic

Constraints:

Protection Type: protected-preferred

Maximum SID Depth: 10

Explicit: segment-list LIST-TO-PE5 (valid)

Weight: 1, Metric Type: TE

SID[0]: 16006 [Prefix-SID, 10.1.1.6]

SID[1]: 16007

SID[2]: 16005

SID[3]: 15005

Attributes:

Binding SID: 24125

Forward Class: Not Configured

Steering labeled-services disabled: no

Steering BGP disabled: no

IPv6 caps enable: yes

Invalidation drop enabled: no

Max Install Standby Candidate Paths: 0

RP/0/RP0/CPU0:PE1#Looking good. Let’s try our traceroute from CE1 to CE2:

CE1#traceroute 192.168.2.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.2.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 2 msec 1 msec 2 msec

2 10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 16007/16005/15005/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec 4 msec 4 msec

3 10.10.67.7 [MPLS: Labels 16005/15005/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec 4 msec 3 msec

4 10.10.57.5 [MPLS: Labels 15005/24407 Exp 0] 4 msec 4 msec 4 msec

5 10.10.58.8 [MPLS: Labels 16003/16004/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec 4 msec 4 msec

6 10.10.38.3 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24407 Exp 0] 5 msec 3 msec 3 msec

7 10.10.34.4 [MPLS: Label 24407 Exp 0] 4 msec 4 msec 4 msec

8 172.16.2.2 5 msec * 5 msec

CE1#It works! We can see the traffic following the P6→ P1 → PE5 explicit path, before entering the P4→P5 dynamic path that avoids red using the 15005 label. The 24407 is the VPNv4 advertised from P4 for 192.168.2.0/24.

As proof of concept we can see that tracing to 192.168.3.50 (loopback1) on CE2, whose BGP route does not have a color 10 attribute, is traversing the normal ECMP path we saw at the beginning:

CE1#traceroute 192.168.3.50 source lo0

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.3.50

VRF info: (vrf in name/id, vrf out name/id)

1 172.16.1.1 4 msec 2 msec 2 msec

2 10.10.16.6 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24409 Exp 0] 5 msec 4 msec

10.10.12.2 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24409 Exp 0] 8 msec

3 10.10.57.5 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24409 Exp 0] 4 msec

10.10.56.5 [MPLS: Labels 16004/24409 Exp 0] 5 msec 4 msec

4 10.10.45.4 [MPLS: Label 24409 Exp 0] 4 msec 4 msec

10.10.48.4 [MPLS: Label 24409 Exp 0] 3 msec

5 172.16.2.2 4 msec * 4 msec

CE1#Here is the final diagram to visualise the result:

So that’s it! There are a lot of different options that SR allows us to use in order to steer traffic intelligently and smoothly across a network. This lab has shown us but one of the methods at our disposal. Further steps might be to implement PCEP for increased scalabilty or introduce more dynamic routing options like performance-measurement – but I’ll leave this variation for a possible later blog.

Thanks so much for reading. Let me know what you think or if you have any comments. Until next time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.